The question “What is good?” served as the basis for the only philosophy course I took in college. I had hoped the course-Philosophy of Art-would explore the artistic impulse that people have to create and would be able to define what distinguishes a good piece of art from one that isn’t.

Unfortunately, the course was neither about art nor about how to distinguish what is good from what isn’t.

Instead, it was a course in semantics that focused on how one talks about art and why art cannot be defined. We talked around subjects, never about them, and therefore never reached a point of understanding or resolution.

A Fragmented Approach

The professor would take a seemingly innocent or benign idea, like goodness and, through a process of analytical reductive reasoning, show us how there is no true idea of goodness. This simple and effective tactic left most of us in the class scratching our heads over the purpose of the class rather than over our beliefs about anything.

For about a decade following that class, I’d find myself, on occasion, dreaming about this professor, about our debates and my changing his mind. I don’t think the professor was so clever to think he’d make philosophers of us students by tearing down our belief systems; rather, I think he was convinced that truth could actually be understood in the analysis of language. Yet that is not true in a universal or values-based sense, but true to the use of the words in that context.

I think the professor was an intellectual nihilist but did not live his life that way. He believed in something, and for him, it was his art and athletic endeavors. Those are what he truly valued. I’m convinced they gave him a social context of friendship through which universal values were evident in their interaction. What I understand today is that my professor’s approach to the subject of that class was small and fragmented; it could not produce the kind of understanding that is whole, the kind of understanding I had been hoping for.

More Than the Sum of Its Parts

When you were a kid, did you ever take apart a toy and then put it back together, only to discover that you had a few remaining parts and so the toy was incomplete? Before you took it apart, the toy was whole-something more than the sum of its parts.

Language is whole; grammar and patterns of word usage are only parts of this whole. For example, say the word “tide,” and it conjures up a range of images. But you don’t know what sort of tide. Add “high” or “roll” to that word, and two very different images come to mind. Words are only part of an idea; they move closer to being complete and whole through the creation of phrases, sentences, paragraphs, essays, chapters, and ultimately books.

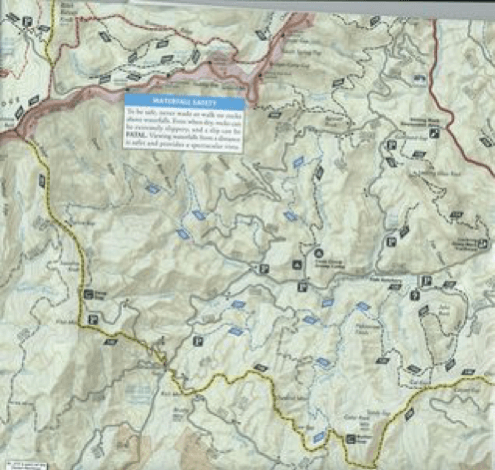

To describe the whole of something is not to describe its parts, but something else. For example, the image below is of a portion of a map of the Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina. For you, it is probably just lines, shading, markers, and names. You know it is a map, but it doesn’t provide much more than that.

The map can serve as a guide, an introduction, to what a person can find at Pisgah National Forest on a visit. However, for those of us who have spent time there, the map represents a whole experience, a complete one.

It is a visual connection to memories of places, people, situations, and experiences we’ve had in the various locations noted on the map. For example, for me, the image of the location of Mount Hardy on the map brings up the image shown below, among others. (Mount Hardy is the peak in the center of the photo.)

On the map, Mount Hardy is just a name of one of hundreds of peaks to climb. Yet, for me, on a June night in 2003, it was a place of fascination and horror as my companions and I watched lightning flash and strike all around our campsite. This place on the map represents wholeness and completeness because the experience will forever stay with those of us who camped there that night.

What Is Good?

I’m convinced that human thought is rationalized emotion. We feel something in response to an experience, and our language provides us with a way to connect with the deeper parts of ourselves we have a hard time expressing without arts and literature. We use visuals to provide a connection between parts of us that are only understandable as something whole and complete.

So, when we say something is good, we are not breaking it down and analyzing its component parts the way we do when we draw a map or look at one. Good is a quality of something that is whole and complete. When we talk about what is good, we are talking about values that capture something that is whole and oftentimes greater than us. To me, these connections represent emergent reality, which I’ve written about previously.

We are not just our thoughts or just our emotions. We are not just a bank of talent or a fulfiller of tasks along an assembly line. We are whole beings who cannot be understood in any complete way by analytical reduction. Our wholeness, rather, is understood as unrealized potential within a particular setting.

When we look at a work of art, we can get really close and examine the artist’s technique; the picture fades and the brushstrokes emerge. Then we step back, and the picture takes on its wholeness again.

What is good about a painting can be described on many levels. For example, there is the technique, the thematic material, the use of color and perspective, and so on. But all of those are only parts of the picture. When they are all combined together, do they create a painting we can say is good? Possibly, but it has a lot to do with the personal values we bring to the experience. And our values are products of our interaction with people in society.

I believe that our lives can be like a painting, excellent in the execution of the brushstrokes and use of color, but even more significant because of the complete picture itself. When we find wholeness in our life and work, we are more than the sum of our daily activities. We become a work of art whose life and work are good.

Doing Good Creates Goodness

Create Goodness is the fifth of the Five Actions of Gratitude I developed and have written about previously. But what does it mean to create goodness?

According to Greek philosopher Aristotle, “Every action and pursuit is considered to aim at some good. . . . what is the highest of all practical goods? It is happiness, say both ordinary and cultured people and they identify happiness with living well or doing well.”

By this, Aristotle means that the actions born from our individual initiative, through our relationships, our work, and the daily course of our lives aim at goodness, which is defined as happiness or living or doing well in life and work. . . .

Contemporary philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, in describing Aristotle’s thought on this point, wrote, “What then does the good for (humanity) turn out to be? It is the state of being well and doing well in being well.”

The word Aristotle uses is eudaimonia (eu-day-mo-knee-a), which is traditionally translated as “goodness.” Its meaning is much more complex than a simple adjective for describing a piece of pie. It touches on ideas related to fulfillment, human flourishing, happiness, and completeness. The good person is one whose whole life is an integrated combination of thought, feeling, initiative, interaction, and action, resulting in a good life, good work, or a better product, community, or world.

The Recipe for A Good Life

The good life is a complete and happy life; it is a life that is complete and whole, fulfilled, meaningful, and makes a difference that matters. It is a life connected to others, just as their lives are connected to ours. And when we find that completeness, our lives are like a painting that evokes values that create goodness and elevate the lives of others. We also become like a map, which is a reference point, an example, of what is possible, and for those who know this, we become a reminder of what the experience of a complete life is like.